June 5, 2023

I had the good fortune to see an exhibition of Vermeer’s paintings at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. Like all great art, they have something to tell us about the world and how we see it. Such insights aren’t mean to stay on the canvas and can help us in our neverending efforts to make sense of situations we find ourselves in.

Vermeer is known for his mastery of perspective, lighting and depth. You’ve probably seen photos or prints of some of his paintings, but to see them up close is qualitatively different. To appreciate them you need to spend some time looking quite deeply and from several different angles. What might seem, when viewed directly from in front, like an undifferentiated dark brown or blue swirl of paint turns out when viewed more roundly to be a garment or carpet full of intricate detail and gradations of light and dark that convey perspective. It contains hidden depth — not hidden by any artifice but hidden in plain sight from the casual glance and yielding only to a more curious and patient engagement.

Vermeer uses light to draw the viewer’s attention to areas he wants to highlight. Again, this is no artifice as the light is carefully observed and falls just where you would expect from the open window. Of course the scenes were staged so that the light would indeed fall in this way. The contrast between the areas that are signposted by the light and the darker ones where we have to work to make out the rich detail is striking but not crude — there is much to be seen in both, and the combination brings out the unique qualities of each more than seeing just light or dark by themselves could do.

The master uses his command of perspective to imbue people and objects with depth and substance. What may be less obvious is that a painting may contain more than one perspective. In Woman writing a letter, with her maid the light from the window in the left of the scene lands on the woman engrossed in her writing. We immediately notice the air of concentration in her face and her firm grip on the pen (further away, in darkness, lies a crumpled earlier version of the letter which we may notice only later as a detail that enriches the story). But there is another perspective: the diagonal row of tiles leading from the foreground to the back of the room points to the maid, who is looking distractedly out of the window and clearly wants to be somewhere else. One picture, two perspectives — one for each person. If you asked each woman what was happening, they’d tell you a different story, and they’d both be right from their point of view. In fact there’s a third perspective, that of the viewer who can see them both and observe the tension between them. That doesn’t mean we’re objective, as if there could be such a thing here — by engaging with the picture we’re also entering into the dance between the wealthy woman and her maid, empathising with one or the other, taking sides or balancing between them. But hopefully we’re aware that that’s what’s going on.By now you must see the general ideas trying to emerge from my account of one exhibition I happened to go to.

Hidden depth: how often do we jump to conclusions about a situation or assume that what we see or hear at the outset is all there is? Of course sometimes that may be right. But in situations that are technically or organisationally complex — or, what is common in my experience, both — there is definitely more to see, demanding a patient eye and the ability to look at the subject from different angles. A tricky problem that I worked on in the payments industry had multiple technical, legal, financial, strategic and operational aspects. There were, as almost always in large companies, multiple stakeholders with different concerns and priorities. It wasn’t a simple splodge of paint, it was a rich tapestry of nuances that had to be teased out.

Light and shade: whether you’re gleaning information from stakeholders or poring over masses of data, there is always conscious or unconscious bias in the selection. Which facts or opinions are highlighted and which are glossed over will tell you something about the people and sources involved and encourage you to ask further questions. Some people may choose not to see or inquire into certain things, some may just not be able to. Either way, as a sensemaker you need to be able to go where others don’t, which starts by being aware that these choices have even been made. Once you do you may uncover a richer picture that may change your view, or the choice of views available to you.

Multiple perspectives: whom you ask for information determines the kind of information you get. Whom you ask to make decisions (or who is expected to by default in the organisational culture) determines the kind of decisions you get. Whether you’re navigating the existing culture and power structures or working on some kind of operating model design, be aware that there is no “view from nowhere”. There will be views based on pay grade or degree of authority, but also views based on ways of working and unique organisational position relative to others. If you’re trying to optimise the interactions between global, regional and country-level teams, or between product and sales teams, any approach that just consists of arrows and boxes, swimlanes and RACI matrices is likely to fall short. You may not be able to get rid of the different points of view but you do have to be aware of them and deal with them skilfully rather than impose your own.

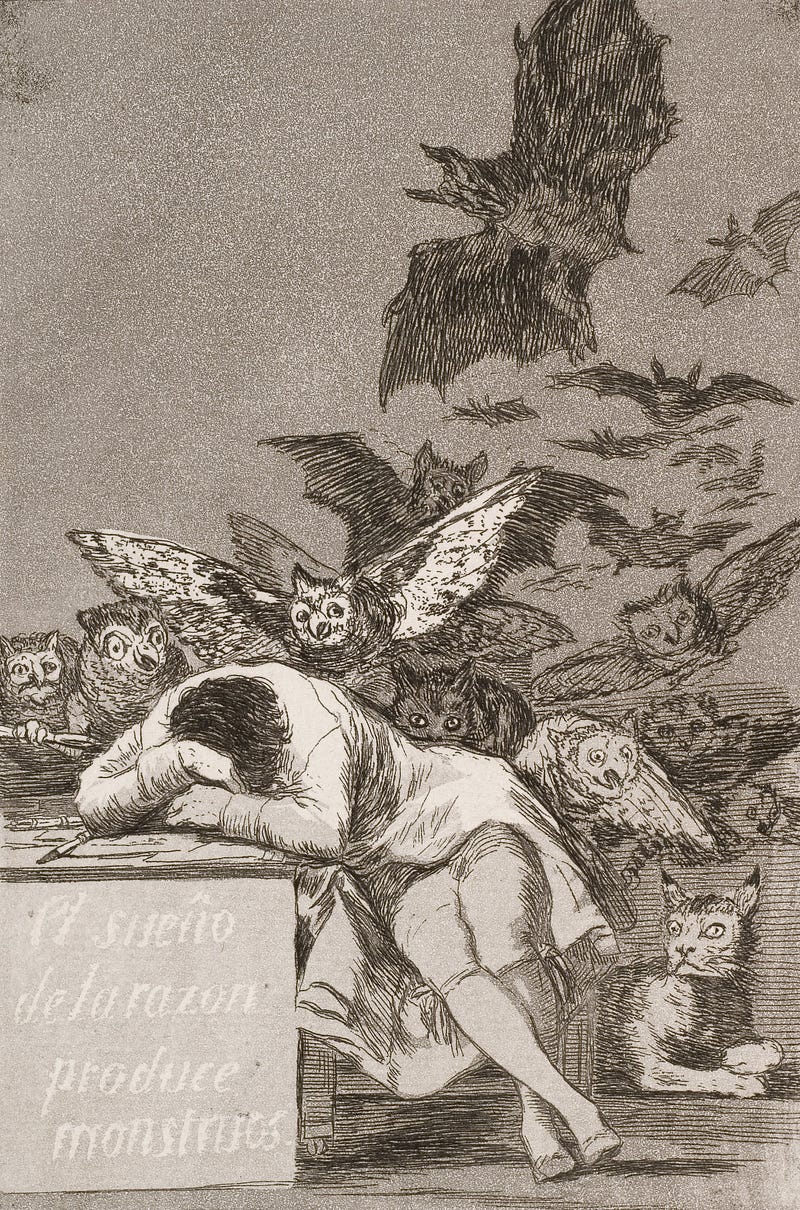

One bonus point. What I’m mainly talking about is how to be a skillful enquirer into situations, like the person who takes their time looking at a painting rather than just getting a snap on their phone and moving on to the next one. In itself, this doesn’t require any knowledge of the subject — and I can tell you I’m not an authority on 17th century Holland — but any expertise you do have can certainly add value. Looking at The lacemaker I was fascinated by the expressiveness in the woman’s face and hands, but I didn’t know anything about the tools she’s using. Luckily I was with my mother, who knows her stuff and was able to tell me all about bobbins. This kind of detailed knowledge is helpful when pressed into the service of the kind of curious, wide-ranging enquiry I’ve been describing. It enhances your curiosity and the insights it can attain. But if you had no curiosity and only vaunted what you already know — “that’s a bobbin! that’s a lute!” you’d learn nothing about what you’re looking at and you wouldn’t enlighten anybody else. This is what Iain McGilchrist means when he calls for pressing the analytical, detail-oriented approach of the left brain hemisphere into the service of the intuitive, holistic approach of the right hemisphere. Of course we need them both, but too often in our data-obsessed world we spend our time counting bobbins and lutes and lose sight of the richer pictures that they’re part of.

Meet the author

Keep reading

-

Complexity eats everything for breakfast

June 9, 2023

I went to a breakfast meeting of business leaders — the kind where everyone has the words “chief” or “head” in their title.

-

Embracing wicked problems

May 17, 2023

A wicked problem is one that isn’t susceptible to linear thinking¹.